Raphael Soyer on Walter Quirt

REMINISCENCES 1932-1968

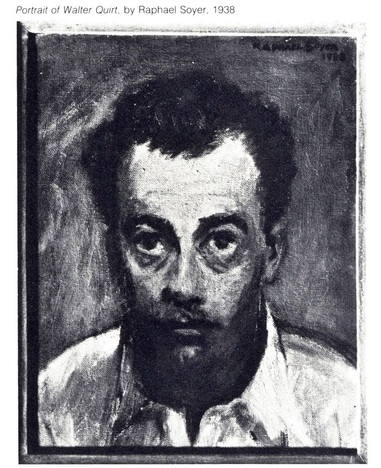

I first knew Walter Quirt when I went with Nicolai Cikovsky to the John Reed Club in the early thirties. Walter, an impressive little guy we called ''Shorty," was then the secretary of the Club. There I made a sketch and a little painting of him.

A lot was going on in the Club, and Walter was one of the most active members. His milieu was among other active members, particularly Charmion von Weigand, Joseph Freeman, Phil Bard, and William Gropper. Although I was a member of the Club, I was never that active, Walter, however, was very active, efficient, businesslike, and somewhat impersonal. He was always carrying this little notebook, an orange paper portfolio with the agenda of the meetings, under his arm. Nicolai Cikovsky would point to Quirt as he was coming into the meeting room with his notebook and say, "Here comes the kantseliarist." He reminded Cikovsky of a character from a novel by Nikolai Gogol. That character was rather discreet, nondescript, and did clerical work. Walter was a very civilized man, never raised his voice as others did in the Club, but did his work in a very quiet way. He didn't play at being an artist.

Although our studios were across the hall from one another in the building at 3 East Fourteenth Street (that building doesn't exist anymore), we each worked on our own. I taught at the American Artists School in the early 1930s and Walter did too. His first wife, Martha Pearse, worked in the office and helped run the school. Walter and I would get together every once in a while. I recall that we were supposed to have lunch with a woman friend, but Walter feared that the restaurant down the street wouldn't admit her because she was black. Since he didn't want her to be embarrassed, we three ate in my studio.

Much of Quirt's early work had to do with the social problems of black Americans, For example, the case of the Scottsboro Boys was a recurrent topic of conversation in the early thirties, and there was always a section in murals reserved for that subject. Sometimes painters would work on murals in groups, and there was a special class at the John Reed Club for murals. In those days everyone was interested in murals, and they were very representational, ~t la Rivera. I remember that I posed for a mural. Members of the John Reed Club would paint each other in the murals, just like Rivera used to do, and they would also include the Scottsboro Boys and portraits of communist leaders.

There was a great Mexican influence in mural painting during this period, particularly the influence of Rivera. It was a loss to this country when his murals for Rockefeller Center were destroyed. I remember that we all picketed Rockefeller Center protesting the vandalism.

Quirt was aggressive in a way. I recall that there was a symposium at The Museum of Modern Art and that Salvador Dali and he were on the same panel. Dali was then at the height of his fame. Those early Dali works were like an electric shock, and he was a very impressive man who spoke with a beautiful, resonant voice. Quirt was almost unknown and talked about art from a Marxian point of view, arguing against Dali's ideas. I was impressed by Quirt's chutzpah.

Walter's earlier works, painted when I knew him in the early thirties, were little paintings, done in tempera, and had hard‑edged forms. They were original and struck me as being very indigenous, possibly to his Midwestern origins. While not absolutely realistic, they were very personal, unlike the work of anybody else at that time. There was something deeply American about them, particularly in light of American history in the 1930s. While I never painted socalled social‑realist pictures‑such as handsome worker/ugly capitalist subjects‑these traits were more evident in Walter's early work because he was involved in social events. The compositions were imaginative and very complex. I can see the old Quirt throughout the later work‑not in the content, but in the rhythm of his compositions.

Raphael Soyer

New York, New York

May 1979

I first knew Walter Quirt when I went with Nicolai Cikovsky to the John Reed Club in the early thirties. Walter, an impressive little guy we called ''Shorty," was then the secretary of the Club. There I made a sketch and a little painting of him.

A lot was going on in the Club, and Walter was one of the most active members. His milieu was among other active members, particularly Charmion von Weigand, Joseph Freeman, Phil Bard, and William Gropper. Although I was a member of the Club, I was never that active, Walter, however, was very active, efficient, businesslike, and somewhat impersonal. He was always carrying this little notebook, an orange paper portfolio with the agenda of the meetings, under his arm. Nicolai Cikovsky would point to Quirt as he was coming into the meeting room with his notebook and say, "Here comes the kantseliarist." He reminded Cikovsky of a character from a novel by Nikolai Gogol. That character was rather discreet, nondescript, and did clerical work. Walter was a very civilized man, never raised his voice as others did in the Club, but did his work in a very quiet way. He didn't play at being an artist.

Although our studios were across the hall from one another in the building at 3 East Fourteenth Street (that building doesn't exist anymore), we each worked on our own. I taught at the American Artists School in the early 1930s and Walter did too. His first wife, Martha Pearse, worked in the office and helped run the school. Walter and I would get together every once in a while. I recall that we were supposed to have lunch with a woman friend, but Walter feared that the restaurant down the street wouldn't admit her because she was black. Since he didn't want her to be embarrassed, we three ate in my studio.

Much of Quirt's early work had to do with the social problems of black Americans, For example, the case of the Scottsboro Boys was a recurrent topic of conversation in the early thirties, and there was always a section in murals reserved for that subject. Sometimes painters would work on murals in groups, and there was a special class at the John Reed Club for murals. In those days everyone was interested in murals, and they were very representational, ~t la Rivera. I remember that I posed for a mural. Members of the John Reed Club would paint each other in the murals, just like Rivera used to do, and they would also include the Scottsboro Boys and portraits of communist leaders.

There was a great Mexican influence in mural painting during this period, particularly the influence of Rivera. It was a loss to this country when his murals for Rockefeller Center were destroyed. I remember that we all picketed Rockefeller Center protesting the vandalism.

Quirt was aggressive in a way. I recall that there was a symposium at The Museum of Modern Art and that Salvador Dali and he were on the same panel. Dali was then at the height of his fame. Those early Dali works were like an electric shock, and he was a very impressive man who spoke with a beautiful, resonant voice. Quirt was almost unknown and talked about art from a Marxian point of view, arguing against Dali's ideas. I was impressed by Quirt's chutzpah.

Walter's earlier works, painted when I knew him in the early thirties, were little paintings, done in tempera, and had hard‑edged forms. They were original and struck me as being very indigenous, possibly to his Midwestern origins. While not absolutely realistic, they were very personal, unlike the work of anybody else at that time. There was something deeply American about them, particularly in light of American history in the 1930s. While I never painted socalled social‑realist pictures‑such as handsome worker/ugly capitalist subjects‑these traits were more evident in Walter's early work because he was involved in social events. The compositions were imaginative and very complex. I can see the old Quirt throughout the later work‑not in the content, but in the rhythm of his compositions.

Raphael Soyer

New York, New York

May 1979